このブログを検索

2025年6月12日木曜日

2024年9月6日金曜日

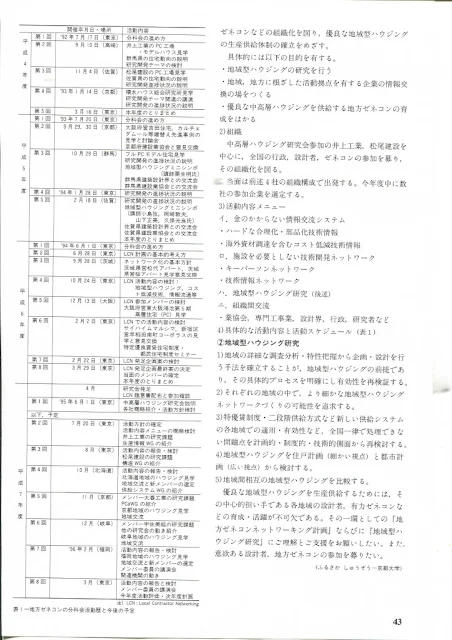

講演:アジアの都市型住宅をめぐって,住環境研究所,19971031

講演:アジアの都市型住宅をめぐって,住環境研究所,19971031

第三期JKKハウジング大学校 シンポジウム

記念講演

『アジアの都市型住宅をめぐって』

布野修司(ふのしゅうじ)

京都大学工学部助教授

●略歴

1949年 島根県出雲市生まれ/松江南校卒/1972年 東京大学工学部建築学科卒

1976年 東京大学大学院博士課程中退/東京大学工学部建築学科助手

1978年 東洋大学工学部建築学科講師/1984年 同 助教授

1991年 京都大学工学部建築系教室助教授

●著書等

『戦後建築論ノート』(相模書房 1981)

『スラムとウサギ小屋』(青弓社 1985)

『住宅戦争』(彰国社 1989 )

『カンポンの世界ーージャワ都市の生活宇宙』(パルコ出版199107)

『見える家と見えない家』(共著 岩波書店 1981)

『建築作家の時代』(共著 リブロポート 1987)

『悲喜劇 1930年代の建築と文化』(共著 現代企画室)

『建築計画教科書』(編著 彰国社 1989)

『建築概論』(共著 彰国社 1982)

『見知らぬ町の見知らぬ住まい』(彰国社 199106)

『現代建築』(新曜社)

『戦後建築の終焉』(れんが書房新社 1995)

『住まいの夢と夢の住まい アジア住居論』(朝日選書 1997)等々

○主要な活動

◇ハウジング計画ユニオン(HPU) 『群居』

◇建築フォーラム(AF)

『建築思潮』

◇サイト・スペシャルズ・フォーラム(SSF)

◇木匠塾

◇中高層ハウジングプロジェクト

◇京町家再生研究会

◇アジア都市建築研究会

◇

●主要な論文

『建築計画の諸問題』(修論)

『インドネシアにおける居住環境の変容とその整備手法に関する研究』(学位請求論文)

はじめに

自己紹介 吉武51C→東洋大→地域生活空間計画 中高層ハウジング

視点:システムを問いたい。一戸一戸建てていくことと基本的空間構成原理

型こそ問題である 型こそが残る? ステレオタイプでいい??

→戦後住宅は型を生みだしたか yes and/or no

no→阪神淡路大震災と戸建て住宅の型:都市型住宅

yes→nLDK

but→nLDKという型のみでいいのか。画一原理

多様性こそ問題:多様性を生み出す原理とは

Ⅰ.戦後建築のゼロ地点

わが住居遍歴・・・プロセスとしての住居

nLDKという共通体験?→変わる変わらない

nLDK家族モデルの成立

公共住宅の住戸形式の変遷

思考実験:ex 都市に寄生せよ:東南アジアのハウジングプロジェクト

多様な住み方 多様な共同生活を可能にする型 型破りの型

一旦、原点に帰って、組立直す必要はないか。

変わるものと変わらないもの

→住宅は保守的 惰性 慣性

農家住宅 床の間 続き間

起居様式 「椅子座」にせよ!というスローガン

ある指針を提示したものが生き残る 定着する?

東南アジアの民家

プリミティブだけれど創意工夫に期待 先進諸国とは別の道

Ⅰ.東南アジアの都市居住

a.東南アジアの都市の特質

○発展途上国の都市化の特質

○発展途上国の都市化過程とその構造

b.インドネシアの都市

○都市形成過程とその類型

○植民地支配と過剰都市化

○ジャカルタの都市形成過程とその構造

c.都市カンポンの構成:スラバヤについて

○スラバヤの都市形成過程とその構造

○カンポンの構成

○カンポン住居の類型と変容プロセス

Ⅱ.東南アジアのハウジング・プロジェクト

○東南アジア各国の住宅政策

○セルフヘルプによるハウジング

○インフォーマル・グループの試み

Ⅲ.東南アジアの伝統的住居

○地域の生態系と住居・集落

○東南アジアの住居の特質

木造住居

高床式住居

切妻転び破風の屋根形態

双系的親族原理

都市住居の伝統の希薄性

分棟形式

○住居空間の構成原理

Ⅳ アジアの都市型住宅

○エコサイクル・ハウス・イン・スラバヤ

○アジアの都市型住宅

日本の住宅 戦後50年

変わるものと変わらないもの

これからの日本の住宅

布野修司(ふのしゅうじ)

京都大学工学部助教授/工学博士

はじめに

自己紹介 吉武51C→東洋大→地域生活空間計画 中高層ハウジング

・『日本の住宅 戦後50年』(資料5)というテキストをもとに話したい。

建築雑誌『戦後家族とnLDK』(資料6)

戦後日本の住宅とはどのようなものであったのか。・・・今後どうあればいいのか。

日本の住宅を歴史的に相対的に位置づけて見たい(戦後50年と阪神淡路大震災)

・具体的な課題は個別に解くしかない・・・直接的に役に立つことはない。

農家住宅 市街化調整区域 Bシステム

大和棟の農村集落景観

→施主とのやりとりのなかから新しい空間を生み出す

システムの適用ではなく、現実からの提案を期待したい

→それぞれの案は、戦後考えられてきた作品の系列にすっぽりと収まっているのではないか。但し、それからはみ出たものは評価されないとしたら問題

思考実験:

ex 都市に寄生せよ、逆噴射家族・・・ 資料7

家族の形と空間の形との基本原理 素材、構造もフリーに考えて問いたい

視点:

システムを問いたい。一戸一戸建てていくしかないけれど、

①基本的空間構成原理、型こそ問題である 型こそが残る

しかし、ステレオタイプでいいということではない。

→戦後住宅は型を生みだしたか yes and/or no

no→阪神淡路大震災と戸建て住宅の型:都市型住宅

yes→nLDK

but→nLDKという型のみでいいのか。画一原理

多様性こそ問題:多様性を生み出す原理とは

多様な住み方 多様な共同生活を可能にする型 型破りの型

一旦、原点に帰って、組立直す必要がある

標準型と変化型 伝統の型と地域の型 型の維持と新たな型の創出

②変わるものと変わらないもの

→住宅は保守的 惰性 慣性

農家住宅が原型(都市型住宅の未成立)

床の間 続き間はなくならなかった

戦後住宅の指針と起居様式 資料8

「椅子座」にせよ!というスローガン 洋服に下駄履きは笑えぬ 文化生活の理想

畳の否定 最もぶざまな下宿屋スタイル 最新!?「住宅読本」 追放された土間

・『日本の住宅 戦後50年』の構成と解説

戦後日本の住宅ベスト10 日本の集合住宅ベスト10・・・資料9

ある指針を提示したものが生き残る 定着する?

1.戦後建築のゼロ地点

わが住居遍歴 資料10・・・プロセスとしての住居

vs 藤森照信の住宅遍歴

若い世代:集合住宅育ち 多様な空間を経験していない

nLDKという共通体験?→変わっていかざるを得ないのではないか

nLDK家族モデルの成立

公共住宅の住戸形式の変遷

思考実験+自己紹介:東南アジアのハウジングプロジェクト スライド

プリミティブだけれど創意工夫に期待

別の道

2.戦後住居と建築家

・・・・・・・戦後住居の指針と未決の問題

建築家と住宅の戦後史

① 床の間追放論 玄関廃止論 最小限住居 ワンルーム モダンリビング

②

③

④

⑤

⑥

⑦

⑧

⑨

⑩

⑪

⑫

1.初期住宅問題と建築家

●新しい目標としての都市と住宅ーーー住宅改良雑感(後藤慶二)/社会 改良家としての建築家/市街地建築物法

●文化生活運動の展開ーーー住宅改良と文化住宅の理想/文化生活運動の 位相/

●民家研究の出自ーーー今和次郎のことなど

●戦争と住宅ーーー西山夘三の国民住居論攷

2.戦後建築の課題としての「住宅近代化」

『戦後建築論ノート』より

●ヒューマニズムの建築ーーー機能主義と素朴ヒューマニズム/近代建築 論争/計画化

●住宅の近代化ーーーこれからのすまい/日本住宅の封建性

●伝統論争と住宅

3.住宅産業と建築家

●都市への幻想ーーー小住宅作家万歳/住宅は芸術である

●マイホーム主義と住宅デザインーーー「都市住宅」派

●都市からの撤退--- 最後の砦としての住宅 自閉の回路

近親相姦の住宅設計

●住宅デザインの商品化ーーー商品化住宅の様式化

3 これからの住まい:日本の課題

日本の都市 その死と再生(This is 読売 199602) 資料11

住宅の問題=都市の問題

nLDKの意義と揺らぎ

nLDK家族モデル 空間化 容器 商品化=工業化

→画一化

戦後住居の論理が欠落させてきたもの

多様性の原理:

家族形態の揺れ=多様化 女性の社会進出

高齢化・・・単身者 コレクティブ・ハウジング

外国人・・・

集住の原理:所有と集合

積層形式における共有空間

歴史の原理:ストック 街並み景観

フローからストックへ

地域性の原理・・・地域住宅生産システムの展望:

直接性の原理

循環性の原理

環境共生

自律性の原理・・・

●棲み分けの構造

地域に生きる建築家と住宅メーカー

メーカーに期待すること

先端モデルの開発・・・ 点ではなく、面のモデル

先端技術:環境共生技術の開発

Ⅴ.住まいと町づくりをめぐる基本的問題

●論理の欠落ーーー豊かさのなかの貧困

◇集住の論理 住宅=町づくりの視点の欠如

建築と都市の分離

型の不在 都市型住宅

家族関係の希薄化

◇歴史の論理

スクラップ・アンド・ビルドの論理

スペキュレーションとメタボリズム

価格の支配 住テクの論理

社会資本としての住宅・建築・都市

◇多様性と画一性 異質なものの共存原理

イメージの画一性 入母屋御殿

多様性の中の貧困 ポストモダンのデザイン

感覚の豊かさと貧困 電脳台所

◇地域の論理 大都市圏と地方

エコロジー

◇自然と身体の論理

人口環境化 土 水 火 木

建てることの意味

◇生活の論理

「家」の産業化

住機能の外化 住まいのホテル化 家事労働のサービス産業代替

住宅生産の工業化 住宅と土地の分離 物の過剰

◇グローバルな視野の欠如 発展途上国の住宅問題

◇体系性の欠如(住宅都市政策)

◇住宅問題の階層化 社会的弱者の住宅問題

2023年9月8日金曜日

スラムとは何か、長澤泰 ・神田順 ・大野秀敏 ・坂本雄三 ・松村秀一 ・藤井恵介編,建築大百科事典, 朝倉書店,2008年

朝倉書店 建築学大百科 1700字×2枚

355 スラムとは何か

スラムSlumとは、「貧民窟」、「貧民街」、あるいは「細民街」のことである。といっても、この訳語そのものが今日では死語に近いからピンと来ないかもしれない。一般的には「不良住宅地」という。要するに、低所得(貧困)層が居住する、狭小で粗末な住居が建並ぶ物理的にも貧しい街区、住宅地がスラムである。

貧しい人々が住む居住地は古来様々に存在してきたけれど、スラムは、近代都市がその内に抱え込んだ「不良住宅地」を指していう。すなわち、産業革命によって、農村を離脱して都市へ流入してきた大量の賃労働者たちが狭小で劣悪な住宅環境に集中して住んだのがスラムである。

スラムという言葉は、スランバーSlumberに由来し、1820年代からその用例が見られる。スランバーとは耳慣れないが、動詞として、(すやすや)眠る、うとうとする、まどろむ、(火山などが)活動を休止する、あるいは、眠って(時間・生涯などを)過ごす、無為に過ごす(away, out, through)、眠って〈心配事などを〉忘れる(away)、名詞となると、眠り、《特に》うたたね、まどろみ、昏睡、[無気力]状態、沈滞という意味である。

スラムの出現は、産業革命による都市化の象徴である。産業化に伴う都市化は、大規模な社会変動を引き起こし、都市と農村の分裂を決定的なものとした。その危機の象徴がスラムである。

いち早く産業革命が進行したイギリスは、マンチェスター、バーミンガム、リヴァプールといった工業都市を産むが、大英帝国の首都ロンドンの人口増加もまた急激であった。1800年に96万人とされるロンドンの人口は、1841年に195万人となり、1887年には420万人に膨れあがる。産業化以前の都市の規模は、基本的には、移動手段を牛馬、駱駝に依拠する規模に限定されていた。火器(大砲)の出現によって築城術は大きく変化するが、新たな築城術に基づくルネサンスの理想都市計画をモデルとして世界中に建設された西欧列強による植民都市にしても、城郭の二重構造を基本とする都市の原型を維持している。産業化による、都市の大規模化、大都市(メトロポリス)の出現は、比較にならない大転換となり、人々の生活様式、居住形態を一変させることになった。

大量の流入人口を受容れる土地は限られており、限られた土地に大量の人口が居住することによって、狭小劣悪で過密な居住環境が生み出されるのは必然であった。全ての流入人口が賃労働者として吸収されないとすれば、失業者や特殊な職業につくものが限られた地区に集中するのも自然である。スランバーは、仕事のない人々が多数無為に過ごす様を言い表わしたのである。

日本の場合、1880年代から1890年代にかけて「貧民窟」=スラムが社会問題となる。有名なのが東京の三大「貧民窟」、下谷万年町、四谷鮫ヶ淵、芝新網町であり、大阪の名護町である。『貧天地飢寒窟探検記』(桜田文吾、1885年)、『最暗黒の東京』(松原岩五郎、1888年)、『日本の下層社会』(横山源之助、1899年)など「貧民窟」を対象とするルポルタージュが数多く書かれている。

スラム問題にどう対処するかは、近代都市計画の起源である。イギリスでは、1848年、公衆衛生法Public

Health Act、1851年、労働者階級宿舎法Labouring Class Lodging Houses

Act(Shaftesbury's Act)、1866年衛生法Sanitary Actが相次いで制定され、1894年にはロンドン建築法によって、道路の幅員、壁面線、建物周囲の空地、建物の高さの規制が行われる。日本では、市区改正などいくつかの対策が1919年の市街地建築物法、都市計画法の制定に結びついている。

スラムは、しばしば、家族解体、非行、精神疾患、浮浪者、犯罪、マフィア、売春、麻薬、・・・など、様々な社会病理[1]の温床とされるが、それは必ずしも普遍的ではない。場合によって生存のためにぎりぎりである居住条件に対処するために、むしろ、強固な相互扶助組織、共同体が形成されるのが一般的である。同じ村落の出身者毎の、また、民族毎の共住がなされ、それぞれに独特の生活慣習、文化が維持される。スラムに共通する、「貧困の文化」(O.ルイス)、「貧困の共有」(C.ギアツ)といった概念も提出されてきた。

20世紀に入って、都市化の波は、全世界に及ぶ。蒸気船による世界航路の成立、蒸気機関車による鉄道の普及は、都市のあり方に決定的な影響を及ぼす。そして、モータリゼーションの普及が都市化を加速することになった。しかし、発展途上地域の都市化は先進諸国と同じではない。先進諸国では工業化と都市化の進展には一定の比例関係があるのに対して、発展途上地域では、「過大都市化over urbanization」、「工業化なき都市化urbanization

without industrialization」と呼ばれる、工業化の度合いをはるかに超えた都市化が見られるのである。ある国、ある地域で断突の規模をもつ巨大都市は、プライメート・シティ(首座都市、単一支配型都市)と呼ばれる。

スラムの様相も、先進諸国のそれとは異なる。第一に、先進諸国のスラムが都市の一定の地域に限定されるのに対して、発展途上国の大都市ではほぼ都市の全域を覆うのである。第二に、スラムが農村的特性を維持し、直接農村とのつながりを持ち続ける点もその特徴である。インドネシアのカンポンkampungがその典型である。

カンポンというのはムラという意味である。都市の住宅地でもムラと呼ばれる、そのあり方は、発展途上国の大都市に共通で、アーバン・ヴィレッジ(都市集落)という用語が一般に用いられる。その特性は以下のようである。

多様性:異質なものの共生原理:複合社会plural societyは、発展途上国の大都市の「都市村落」共通の特性とされるが、カンポンにも様々な階層、様々な民族が混住する。多様性を許容するルール、棲み分けの原理がある。また、カンポンそのものも、その立地、歴史などによって極めて多様である。

完結性:職住近接の原理:カンポンの生活は基本的に一定の範囲で完結しうる。カンポンの中で家内工業によって様々なものが生産され、近隣で消費される。

自律性:高度サーヴィス・システム:カンポンには、ひっきりなしに屋台や物売りが訪れる。少なくとも日常用品についてはほとんど全て居ながらにして手にすることが出来る。高度なサーヴィス・システムがカンポンの生活を支えている。

共有性:分ち合いの原理:高度なサーヴィス・システムを支えるのは余剰人口であり、限られた仕事を細分化することによって分かち合う原理がそこにある。

共同性:相互扶助の原理:カンポン社会の基本単位となるのは隣組(RT:ルクン・タタンガ)-町内会(RW:ルクン・ワルガ)である。また、ゴトン・ロヨンと呼ばれる相互扶助活動がその基本となっている。さらに、アリサンと呼ばれる民間金融の仕組み(頼母子講、無尽)が行われる。

物理的には決して豊かとは言えないけれど、朝から晩まで人々が溢れ、活気に満ちているのがカンポンである。そして、その活気を支えているのがこうした原理である。このカンポンという言葉は、英語のコンパウンド(囲い地)の語源だという(OED)。かつてマラッカやバタヴィアを訪れたヨーロッパ人が、囲われた居住地を意味する言葉として使い出し、インド、そしてアフリカに広まったとされる。

「スラム街」という語を和英辞典で引くと興味深い。バリアーダbarriada(中南米、フィリピン)、バスティbustee, busti, basti(インド)、、ファヴェーラfavela(ブラジル)、ポブラシオンpoblacion(チリ)などと、国、地域によって呼び名が異なるのである。ネガティブな意味合いで使われてきたスラムという言葉ではなく、それぞれの地域に固有の居住地の概念として固有の言葉が用いられるようになりつつある。

問題は、究極的に、土地、住宅への権利関係、居住権の問題に帰着する。スクオッターsquatter(不法占拠者)・スラムという言葉が用いられるが、クリティカルなのは、貧困のみならず、戦争、内戦などによって生み出される難民、スクオッター、ホームレスの問題である。差異を原動力とし、差別、格差を再生産し続ける資本主義的な生産消費のメカニズムがスラムを生み出す原理である。すなわち、物理的なスラム・クリアランスが究極的な意味でのスラムの解消に繋がるわけではないのは明らかである。その存在は、各国、各地域の政治的、経済的、社会的諸問題の集約的表現である。

2023年4月5日水曜日

2023年2月2日木曜日

ジャイプルのハヴェリ,雑木林の世界58,住宅と木材,(財)日本住宅・木材技術センターセンタ-,199406

ジャイプルのハヴェリ,雑木林の世界58,住宅と木材,(財)日本住宅・木材技術センターセンタ-,199406

雑木林の世界58

ジャイプールのハヴェリ

布野修司

飛騨高山木匠塾の第4回インターユニヴァーシティ・サマースクールの今年の日程が、八月三日から一一日と決まった。八月六日が日本一かがり火祭りで、今年も屋台を出店することになる。施設計画も進められつつあり、財源についても検討しつつあるところだ。プログラムについては、ほぼ昨年と同じとなることを想定しているが、詳細は未定である。 ●期間 一九九四年八月三日(水曜)~八月一一日(木曜)

●場所 岐阜県高根村久々野営林署野麦峠製品事業所

●主催 飛騨高山木匠塾(塾長 太田邦夫)

●後援 名古屋営林局・久々野営林署/日本住宅木材技術センター/高山市/高根村/AF(建築フォーラム)/サイトスペシャルズフォーラム/日本建築学会/日本建築セミナー/木造建築研究フォーラム(以上 予定)

○実習

1。屋台模型制作実習 1/5および原寸部分/2。家具デザインコンペ /3。家具制作/4。足場組立実習/5。施設全体計画立案/6。野外風呂建設

/7。バイオガス・浄化槽研究/8。竈建設/9。測量実習 /10。型枠実習

●参加資格 木造建築に関心をもつ人であれば資格は問わない

●参加予定 芝浦工業大学・東洋大学・千葉大学・京都大学・工学院大学・大阪芸術大学・京都造形大学・茨城ハウジングアカデミー

●参加費 学生 3000円/日(食事代、宿泊費含む)/一般 5000円/日(食事代、宿泊費含む)/但し、シーツ、毛布、枕カヴァーは各自持参のこと。

●連絡先 芝浦工業大学 藤澤研究室( )/京都大学 西川・布野研究室( )/千葉大学 安藤研究室( )/東洋大学 太田・秋山・浦江研究室( )

さて、この春休みにはタイとインドに出かけてきた(三月二〇日~四月五日)。タイは、AIT(アジア工科大学)でレクチャーを行なう以外は特に目的はなかったのであるが、久しぶりにバンコク、チェンマイ、アユタヤを見ることができた。特に懐かしかったのは、ビルディング・トゥゲザーのプロジェクト・サイトを再訪できたことである。このプロジェクトは、インターロッキング・ブロックとPCの梁を組み合わせるビルディング・システムにより、居住者自ら建設に参加する形をとったユニークな試みであったが、その変貌は驚くほどであった。タイの経済水準は随分と高くなった、という印象である。

ブロック造のニュー・ヴァージョンは、カナダからのルファブル先生を中心とするAIT(ハビテック・パーク)と協力して続けられているのであるが、供給形態としては建て売りの形である。ビルディング・トゥゲザーも変質を迫られたようである。

本命は、インドのジャイプールであった。インドは初めてである。デリー、チャンディガール(コルビュジェも迫力あるけれど、ロックガーデンもいい)、アーグラ(タージマハール!!)、ファテプルシークリー(アクバルの建築狂)、マトゥラ(クリシュナの聖地)とムガールの都市建築を見て、ジャイプールへというコースである。ジャイプールには、研究室の荒仁(アラジン)君が二月の初めから滞在しており、同じく研究室の青井哲人君と調査の仕上げに駆けつけたというかたちであった。

ジャイプールと言えば、例のジャンタル・マンタル(天文台)がある。デリーのものより規模が大きい。建築家毛綱毅曠、写真家藤塚光政が組んで出した『不知詠人読み人知らずのデザイン』(TOTO出版 一九九三年)にも取り上げられている。見るのが楽しみであった。しかし、町の方がさらにすごい。興味は、都市計画と都市住居の方にすぐさま移ったのであった。

ジャイプールの町を計画したのも、ジャンタル・マンタルをつくったジャイ・シンⅡ世である。一八世紀の前半のことである。実際に都市計画に当たったのは、ビジャダル・ナガルであり、ジャイプールはビジャダル・ナガルの町とも呼ばれる。

その形態は極めて特徴的である。基本は三ブロック×三ブロックのナイン・スクエアなのであるが、北西部が山によって切りとられ、その分、南東部が一ブロックはみ出している。全体は、ヴァストゥ・プルシャ曼陀羅、あるいは、インド古代から伝わる建築書マナサラのプラスタラ・タイプに基づくという説がある。奇妙なことに正南北に対して都市軸がずれている。諸説あるけれど、ジャイプールがあるコスモロジーに基づいて理念的計画された計画都市であることは明かである。

一辺が八〇〇メートルの一ブロック(チョウクリ)はかなりのスケールである。城壁で囲まれたピンク・シティ(旧市街:建物は赤い砂岩でつくられ、町全体が赤いことからこう呼ばれる)は想像以上に大きい。しかし、住民にとって、このスケールは極めて適切であるということが、歩き始めてすぐにわかった。ブロックの通りには、ありとあらゆる店が並ぶ。幹線道路が交わる交差点は、チョウパルと呼ばれ、マーケットになっている。また、ブロックの内部では様々なものがつくられている。最大でも四〇〇メートル歩けばたいていのものは手に入る。職住近接である。住工混合である。様々な機能が重層しあっている。

一階にはショップ、その後ろには事務所スペースが置かれる。三階、四階である。その背後に居住スペース。立体的な断面構成も重層的である。しかし、きちんとした型がある。中心になるのは、ハヴェリと呼ばれる中庭形式の住居である。中庭を囲んで、オフィスや店舗がつくられる場合も多い。

ハヴェリとは邸宅の意であるが、チョウクと呼ばれる中庭を囲んで三層、四層の構成をとる。グジャラートでは、木造であるが、ジャイプールでは組石造である。何人住んでいるか、と問えば百二十人とか、百三十人とか、答が返ってくる。我々には想像ができないかもしれないのであるが、いわゆるジョイント・ファミリー(合同家族)である。屋上は日が落ちれば実に涼しい空間になる。ハヴェリは、高密度居住が可能になる都市型住居である。調査の分析が楽しみである。

2022年11月12日土曜日

2022年11月1日火曜日

2022年9月19日月曜日

町家再生というテーマ,日経アーキテクチャー,19940221

日経アーキテクチャー 「建築選集93」

町家再生というテーマ

布野修司

「先生の家ーーーご近所からも、教え子たちからも、「先生の家」と親しみを込めて呼ばれる住まいを○○ホームがお手伝いします」、「住まいは、人柄や仕事柄を写し出す、もうひとりの「先生」です。先生らしい夢とこだわり。○○ホームは大事にします。先生のためのこだわり空間」。

バブルが弾けてめっきり減った住宅販売のDMやチラシ広告が再び増え出している。金利が史上最低とかで住宅市場が動き出しているらしい。バブルが弾けたとはいえ年間140万戸近く新設住宅があるのは確かである(そう変化はなさそうなのだが、実態はかなり激変である。新設の建設戸数の多くは木造賃貸アパートという分析もある)。しかしそれにしても、先生(公務員)は固いというのであろうか、上のDMは宿舎住まいのわが身には強迫じみていていささかきつい。

住宅業界のこの間の変化については、松村秀一の「景気変動と住宅」(『建築思潮』02号)に的確な分析がある。コスト問題、「多様化ー標準化」問題、「技能者問題」、「所有問題」の見直しに多くの問題が残されていることが指摘されている。

ところで、建築家はどうか。不況になればじっくり住宅設計というのがパターンなのであるが、どうだろう。60年代末から70年代にかけて、「都市から撤退」を迫られた建築家たちは住宅を「最後の砦」に「近代建築批判」の策を練ったのであるが、そして、バブル経済とともにポスト・モダンの百花燎乱を咲かせたのであるが、この世紀末へ向けてはどうなのか。

その方向についてはかなり心もとない(ウサギ小屋のうすら寒い実態は依然としてあるのだ)が、まず、目立つのは環境共生住宅、エコ・ハウス、省エネ・省資源・リサイクルのかけ声である。また、地域住宅計画の流れである。さらに、木造住宅復興のスローガンである。奇を衒うった形態のアクロバティックはなりをひそめた。

しかし、例えば、エコ・ハウスが確固として流れになりつつあるかというとそうでもない。第一、エコ・ハウスがどのようなものになるのかまだはっきりしないのである。また、例えば、西欧で現実化されつつあるものがコスト的に合わないということもある。さらに、必ずしもデザインの問題になっていないということがある。考えてみれば、今日の住宅にかかわるテーマは既にオイルショック以降問われ続けてきたものであり、ようやく、真剣な取り組みがなされ始めたという感が強い。

建築家にとっての課題と言えば都市住宅がある。新しい形の都市型住宅のモデル、プロトタイプを創り出すという任務である。コレクティブ・ハウジングのような新しい居住形態が日本にどう定着していくか、コーポラティブ住宅が今後どう展開していくかにも関わるテーマである。

そして、もうひとつ気になるテーマがある。木造町家の再生である。京都で「京町家再生研究会」(1992年7月発足)に加えて頂いたせいもある。また、「町家再生のための防火手法に関する調査」研究を横尾義貫先生から仰せつかったせいもある。京都のような町家のストックがある都市(『建築文化』1994年2月号参照)でこそ、新しい都市型住宅が生み出されなければならないと思うのであるが、木造の町家について、それを再生するには余りにも壁が分厚い。既存ストックとしての木造町家を活用しようとしても、リサイクル資源としての木造を有効活用しようとしても、それを阻む法制度がある。また、木造の町家を否定し続けてきた価値観も強大である。何も木造に拘る必要はないのだが、都市が生き続けていくための空間的仕掛としての住居のあり方が町家の再生のトライアルの中で見えてくる筈だ、というのが直感である。

布野修司 履歴 2025年1月1日

布野修司 20241101 履歴 住所 東京都小平市上水本町 6 ー 5 - 7 ー 103 本籍 島根県松江市東朝日町 236 ー 14 1949 年 8 月 10 日 島根県出雲市知井宮生まれ 学歴 196...

-

traverse11 2010 新建築学研究11 Ondor, Mal & Nisshiki Jutaku(Japanese Style House):Transformation of Korean Traditional House オンドルとマル,そして日式住宅...

-

進撃の建築家 開拓者たち 第 11 回 開拓者 13 藤村龍至 建築まちづくりの最前線ー運動としての建築 「 OM TERRACE 」『建築ジャーナル』 2017 年7月(『進撃の建築家たち』所収) 開拓者たち第 12 回 開拓者 14 藤村龍至 ...